(Original article from Harvard Health Publications)

Published: July, 2011

The same vision changes that make you eager to toss your glasses or contacts can complicate your decision about surgery.

Even if you’ve worn glasses or contacts for decades, you may be wondering about having your vision surgically corrected. Your contacts may feel less comfortable; perhaps you hate wearing reading glasses; or maybe you finally have the money to seek an instantly clear view of the world as you wake in the morning or pop your head out of the swimming pool. But how advisable is laser vision correction in your 50s, 60s, or beyond?

If your eyes are otherwise healthy, laser refractive surgery may provide the results you’re looking for. But the risks and benefits do shift around midlife, so you need a thorough evaluation and a frank assessment of what you might gain — or lose.

Types of laser refractive surgery

Two structures, the lens and the cornea (the clear dome at the front of the eye), bend light to focus it on the retina, the light-sensitive tissue at the back of the eye. Laser refractive surgery corrects vision by reshaping certain layers of the cornea. It’s an outpatient procedure performed while your eyes are numbed with a topical anesthetic.

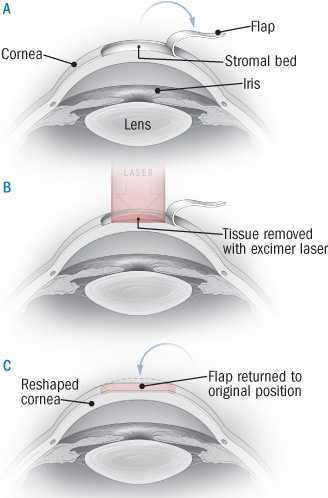

Surgeons have several different ways of gaining access to the corneal layer being treated. The best-known is LASIK (laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis), in which a precision instrument — either an automated microkeratome or a newer, bladeless device called a femtosecond laser — cuts a thin flap from the outer cornea, leaving one side attached like a hinge. The flap is folded out of the way, a pre-programmed laser reshapes the inner cornea to correct your vision, and the flap is returned to its original position (see “What happens during LASIK surgery?”). No stitches are needed.

A number of LASIK alternatives, known as surface ablations, disturb only the surface of the cornea (the epithelium) before applying the laser. In photorefractive keratotomy (PRK), a section of epithelium is completely removed with a laser. In LASEK (laser epithelial keratomileusis), an alcohol solution is applied to weaken and loosen the epithelium so the surgeon can gently move it aside and reposition it after the vision correction. In epi-LASIK, a thin sheet of epithelium is removed with a special microkeratome and set aside (it may or may not be repositioned after surgery). After surface ablation procedures, a soft contact lens is applied to protect the cornea while it heals (usually in three to seven days).

The choice between LASIK and surface ablation procedures depends on your eyesight, the thickness of your cornea, and any medical conditions you may have.

“For the lowest correction, we often recommend surface ablation because a flap is potentially more prone to trauma, infection, and a need for retreatment. For high corrections, we usually recommend LASIK because the visual outcomes are better,” says Dr. Roberto Pineda, assistant professor of ophthalmology at Harvard Medical School and director of refractive surgery at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

What happens during LASIK surgery?

Laser-assisted in situ keratomileusis, or LASIK, is the most commonly performed laser refractive surgery. After the eye is numbed, a microkeratome (which works like a carpenter’s plane) or femtosecond laser creates a flap about the size of a contact lens from the corneal epithelium and stroma (middle layer of the cornea). The flap is folded back to expose the stromal bed (A). An excimer laser removes a precise amount of the stromal bed (B). The flap is then returned to its original position (C). No sutures are needed.

Getting an evaluation

Look for an ophthalmologist with extensive experience performing the procedure and up-to-date equipment (less than 10 years old). If possible, choose one who has had fellowship training in laser refractive surgery.

Before your evaluation, you’ll need to go without contacts for a while (one to two weeks if you wear soft lenses; three to four weeks if you wear hard lenses) because they distort the shape of your corneas.

The surgeon will thoroughly evaluate your eyes, including the shape, thickness, and condition of the corneas; tear production; refractive errors (nearsightedness, farsightedness, and astigmatism); the size of your pupils (pupils that become very large in dim light are more prone to glare, halos, and double vision following refractive surgery); and the presence of other eye conditions that become more common with age. Because you have to focus on a light while the laser is applied, you must demonstrate that you can stare at a single point for at least 60 seconds.

Your surgeon also needs to know about your general health and any medications you are taking. Surgery may be inadvisable because of an autoimmune disease or another condition that makes you more prone to infection. You may have to stop taking certain drugs that impair wound healing (such as steroids), cause dry eye (such as certain antidepressants and blood pressure pills), or create vision difficulties (such as the heart medication amiodarone).

A frank discussion

Most people are satisfied with the results of laser refractive surgery, but it’s important to recognize possible problems and have realistic expectations.

After surgery, vision can take weeks to months to stabilize. These days, about 75% of patients achieve 20/20 or better distance vision (ability to read on the eye chart what a person with normal vision should see from 20 feet), and more than 95% achieve at least 20/40 vision (good enough to pass a driver’s test, equivalent to being able to read from 20 feet what the person with normal vision could read from 40 feet). But even a 20/20 result on an eye test may not mean perfect vision in real life, because you may develop problems with night vision or difficulty distinguishing between shades of gray. Some people wear rigid gas-permeable contacts because their vision is clearer that way than with glasses or soft contacts. If you’re one of those people, the ophthalmologist may raise a yellow flag, because laser refractive surgery often can’t match that crisp, non-distorted view.

After surface ablation, you may feel discomfort, burning, and scratching as the epithelium heals. Dry eye is common after laser refractive surgery; it usually improves in a few months but becomes long-lasting in more than 20% of patients, with symptoms ranging from mild to extremely bothersome. Immediately after surgery, you may notice glare, halos, or double vision, especially at night. These symptoms persist for more than six months in up to 20% of patients, although studies indicate that only about 5% are actually bothered by them.

Other possible problems include the development of a new astigmatism, reduced ability to see contrasts, and under- or over-correction requiring glasses or further surgery. The surgical site can become infected; the inner cornea can become inflamed, causing hazy vision (this is more common after surface ablations); and in LASIK or LASEK, the flap can dislodge or become wrinkled.

Inform yourself thoroughly about the risks (see “Selected resources”), and make sure all your questions are answered before you make a decision.

Refractive surgery meets the aging eye

Age alone isn’t a big factor in deciding whether to have refractive eye surgery. A Harvard ophthalmologist, reviewing results on 424 LASIK patients in their 40s, 50s, and 60s, found that although older patients were slightly more likely to fall short of the best results and slightly more likely to need repeat treatment, or “enhancement,” outcomes in general were similar regardless of age.

Nevertheless, various age-related eye conditions can influence your decision on laser vision correction. These conditions, listed below, may need to be diagnosed and treated differently in someone who’s had laser eye surgery:

Cataracts. With age, the lens of the eye can become clouded, a condition called cataract. Most people have some opaqueness in their lenses by age 60. Cataract occurs in about half of people ages 65 to 74 and in 70% of those ages 75 and over. When cataracts cause symptoms — blurriness, poor night vision, or distorted colors — the clouded lens can be removed and an artificial one implanted, often restoring normal sight to lifelong glasses-wearers.

Laser refractive surgery does not prevent or slow the development of cataract, so a later cataract will mean another surgery. For this reason, if there’s any sign of clouding, your ophthalmologist may recommend waiting and having your vision corrected through cataract surgery.

But if you’ve already had refractive surgery, it’s trickier to choose the correct lenses for cataract surgery, so if you undergo one of these laser vision procedures, ask your ophthalmologist to fill out an American Academy of Ophthalmology “K card” (available at www.health.harvard.edu/kcard) indicating your refraction before and after surgery. If you ever need cataract surgery, this information will assist in selecting a lens.

If you have residual nearsightedness after cataract surgery, laser surgery (usually PRK) can sometimes be performed to sharpen your distance vision.

Glaucoma. Glaucoma is caused by increased fluid pressure within the eye that impinges on the optic nerve. Untreated, it can result in blindness. In the early stages, glaucoma causes no symptoms, so ophthalmologists screen for it by checking intraocular pressure and looking for optic nerve damage. Laser refractive surgery thins the cornea, leaving it softer and more flexible, so subsequent glaucoma screenings will show lower intraocular pressure readings. That may result in failure to diagnose early glaucoma. Make sure your ophthalmologist knows if you’ve had laser vision correction so that when monitoring for glaucoma, she or he can use special conversion tables that take your corneal thickness into account. An FDA-approved device (TonoPach) is available that simultaneously measures intraocular pressure and corrects the results to adjust for the thickness of the cornea.

LASIK is inadvisable if you have moderate or severe glaucoma because your treatment will become more difficult to monitor. Also, intraocular pressure temporarily spikes during the procedure (suction is required to hold the cornea as the flap is cut). But if your glaucoma is mild and easily managed with a single medication, you may still be a candidate for laser vision correction.

Dry eye syndrome. With age, your eyes tear less, and you may notice an itching, burning, or scratching sensation that results from decreased lubrication. This problem is more common in women and often starts after menopause. Contact lenses may become less comfortable, which heightens the appeal of laser refractive surgery.

But if you have severe dry eye, you shouldn’t undergo the procedure. Cutting the corneal flap in LASIK severs nerves involved in tear production, and dry eye is a common result (affecting about 50% of patients). Dry eye following laser refractive surgery techniques that don’t involve a flap is less common, but if you already have dry eye, the corneal surface may heal more slowly. That means you should have your tear production measured before you decide whether to undergo laser refractive surgery. If it’s below a certain level, you should probably avoid the procedure because you are more likely to develop chronic dry eye afterward.

Presbyopia. In your 40s and 50s, the lens of the eye naturally becomes more rigid and less able to focus clearly on near objects. The usual way to accommodate this change is to wear reading glasses — or bifocals, trifocals, or progressives. You can also wear contact lenses that correct one eye for distance and the other for near vision, an approach called monovision.

Laser refractive surgery doesn’t prevent presbyopia. If you have the procedure in your 40s, you’ll still likely develop the need for reading glasses within the next 10 years or so. Maybe you’re myopic and currently take off your glasses for close-up tasks, such as threading a needle, thus taking advantage of your natural nearsightedness. That strategy will no longer work after laser vision correction.

To address presbyopia, the surgeon can correct one eye for distance vision and the other for closer work, producing the same effect as contacts for monovision. But most people can’t adjust to having one eye that’s blurry all the time. To find out if you can tolerate it, your ophthalmologist may have you wear contacts that simulate the correction for a while (or simulate the correction in the office, though this won’t give your brain a chance to adjust). The stronger your reading glasses — and therefore the greater the difference between the correction required for your right eye and your left eye — the more likely you are to experience diminished depth perception. To minimize the discrepancy, your ophthalmologist might suggest correcting one eye for distance and the other for intermediate vision, an approach called blended vision or mini-monovision. This should allow you to clearly see your computer screen, piano keys, or car dashboard, but you’ll still need glasses for reading.

“Even if you have one eye corrected for near vision, you may still be more comfortable wearing glasses for prolonged reading,” says Dr. Ula Jurkunas, assistant professor of ophthalmology at the Massachusetts Eye and Ear Infirmary.

A new presbyopia technique now offered in Europe is undergoing a three-year study in the United States. Instead of removing tissue from the mid-cornea, the surgeon cuts a flap in the cornea of one eye and inserts a removable inlay (brand name AcuFocus). It’s a ring less than one-quarter the size of a soft contact, with a tiny hole in the middle that creates a pinhole effect (much like squinting or an early camera) to increase the depth of focus and sharpen near and intermediate vision.

Improvements in the lenses used for cataract surgery have provided another surgical option for people with presbyopia — albeit one that is controversial and not approved by the FDA. Variable-focus implantable lenses enable people who undergo cataract surgery to see objects at various distances. Some ophthalmologists are now using these lenses to replace the natural lenses in people who are middle-aged or older who have the beginnings of cataracts that aren’t yet affecting their vision and who rely on glasses or contact lenses for presbyopia. But this surgery is not covered by insurance unless you have cataracts, and the cost can be as high as $5,000 for each eye. Also, many ophthalmologists are reluctant to perform the procedure in people without cataracts because of the risks and lack of information about long-term safety and effectiveness.